On Bullying, Jealousy and the Complications of Friendships

I often write about books kids love, but I think there are some books that love kids back. In Wonder, a YA novel written about a boy with facial differences, author R.J. Palacio says: “Much has been written about middle school and the preteen years, and how it’s a time in kids’ lives when they are almost expected to be unkind to one another as they navigate their way through new social situations on their own, often without parental oversight. But I’ve seen a different side to kids – a tendency toward nobility, a yearning to do right.” Like Mister Rogers, like bell hooks, R.J. Palacio believes in “children and their limitless capacity to care and to love and to want to save the world”. The wisdom of children is monumental: “I hate money!” one of my sons says regularly and with vehemence. “It’s just paper printed with pictures and it hurts trees. If I meet the person who invented money I want to punch him in the face.” And isn’t this so true? Don’t we continue to worship all the wrong things?

It is trite to say that bullies are bullies because they are insecure, because they are afraid, because they have been mistreated and feel misunderstood and alone and lonely. Bullying itself is a misnomer. When we say bullying what we often mean is something systemic. Bullying too often fills in for “I am being left out because I am vulnerable due to my race/class/gender performance”. We need ways of talking about bullying that get at its nature.

In Hysterical, which should be required reading for everyone who has to go to a doctor, which is to say, everyone, Elissa Bassist talks about trying to talk as a woman so that you fit in and won’t be bullied. This form of speech is a verbal feat that defeats her. Bassist describes this impossible doublespeak:

“If only I could move my voice into the impossible right sound that is likeable and pleasing, educated but not snotty, and that grew up in a suburb, then moved to a city, then moved back to the suburb. It doesn’t protest too much . . . . It’s tuned in to others and makes everyone else’s life easier. If it were a size it would be a size small. And it admires jokes but doesn’t but doesn’t make any. The right voice . . . . [is] “A sexy baby voice. . . . horny yet nonconfrontational. . . defenseless and signal[s] that I must be protected and coddled and burped. . . . Vocally and weight-wise, infancy is apparently a woman’s sexiest time”.

Images from Virginia Wolf, written by Kyo Maclear and illustrated by Isabelle Arsenault

In a classroom today I asked 6 year olds to draw both boys and girls. Draw a boy and a girl doing something that “the world tells them they shouldn’t do but that you think they should be allowed to do.” I drew a boy crying and a girl getting mad. Girls drew boys dancing ballet and girls playing soccer. They drew girls marrying girls and boys growing long hair. The boys mostly drew themselves going into the girl’s bathrooms, and when one boy protested with tears in his voice ("no! it's something we think we should be allowed to do, not just what we want to do to make the girls mad"), he was told by another to stop crying, it was a joke. That’s bullying, and it’s also patriarchy. And, for a lack of a more articulate term, it just also sucks. It should really be called patriarchal bullying.

While I tried to read the class a book on the tough guise of masculinity, I heard girls endlessly trying to assert themselves without assertions, in what seemed like a form of talking without communicating. It reminded me of a book a friend of a friend of mine was reading, called How To Change Your Marriage Without Talking About It, which I had to look up to believe it was real. These girls were in grade 1 and they were talking about kissing:

Girl 1: "I think I want to kiss (let's call him Soccer Boy)."

Girl 2: “Well, it’s ok to want to kiss Soccer Boy if you want to marry him.”

Girl 3: "Can you want to kiss him without marrying him if you only kiss him on the cheek?

Girl 2: “Oh no!” (Girl 1 was being slut-shamed).

Girl 3: "Do you still want to kiss Soccer Boy?"

Girl 1: "Yes, well no, kind of but not really.”

This is the actual dialogue, I wrote it down. I couldn't make this up; who could remember this many non-sentences? At 6, these girls have internalized and vocalized that no sentence that did not end in a question mark about kissing was safe enough to say, and probably what was safest was silence.

Be nice, don’t get angry, edit oneself or don’t speak. Is it any surprise that girls turn on one another in the desire to let the rage out? The truth is that this is patriarchal rage, but misdirected at each other. I have been looking to picturebooks to help us find a way back to ourselves and each other. If we are going to be systemically divided against one another, I know we can systematically find a way back to each other. The books below help to name these disconnections so that we might do so.

My Bestfriend, Sometimes

by Naomi Danis, illustrated by Cinta Arribas

This book is by the incomparable Naomi Danis and Cinta Arribas, who gave us the absolutely brilliant book I Hate Everyone which I reviewed previously here. This friendship begins the way so many do: “If you give me a cookie, [Stephanie] said to me, “I’ll be your best friend. I gave her a cookie”. Describing the way that they like to hang out, Danis perfectly captures the cadence of their age: “Stephanie and me. What do we like to do. Sit next to each other. Talk…..Run at recess. Play pretend. Pretend I’m the mother and you’re the baby. Pretend I’m the doctor and you need a shot.” Even though these two whisper secrets that they share with nobody else, “Stephanie and I like each other. And we don’t like each other. Both.”

This book’s illustrations pose questions about racist bullying in friendships. Stephanie is white, and our hero is racialized. We are left to wonder if racism is inflecting Stephanie’s challenging treatment of her friend, and hence the systemic nature of bullying. For instance: “I get new shoes and Stephanie doesn’t tell me she likes them. My mom says I should be glad that I like my shoes and Stephanie likes her shoes. It’s not important, my mom says, for Stephanie to like my shoes. But still, I wish she would, and I wish she would tell me.” Or “Stephanie brings my favorite candy to school and doesn’t save a piece for me, even though she knows I like it because I always ask her for some. “Sorry,” she says. “Today I just feel like eating it all up myself.” Well, at least she said sorry.”

Oh, how my heart hurts for these this girl. Who hasn’t been on the rollercoaster of the ups and downs of a fickle best friend. There was a friendship triad in my son’s class that I watched with much interest: it seemed quite excruciating. Endlessly, the girls struggled about who would be who in a game of Family. “I don’t want to be the brother,” said one girl with such pain in her voice, until finally the lead girl caved and agree she could be a sister. Although ostensibly nothing was happening, I could see just how painful the conversation was. I was trying to read a book about “being a good neighbour” and I could tell just how out of step I was with the worlds of the children around me. I wished so much I had brought My Best Friend, Sometimes to read instead. Especially since in the book, like in life, things go south.

“One day Stephanie is mad at me, so mad that she isn’t talking to me. But because we are best friends, she sits next to me on the school bus anyway, not talking to me all the bumpy way home. I can’t even remember what her mad is about. Is she mad because it will be my turn to take the guinea pig home this weekend and she wants it to be her turn? I don’t know. She won’t tell me. I feel sad. And confused."

Recently I was mad at my partner in the car. I didn’t and still don't know why! I felt hot and uncomfortable, consciously trying to hold the words back that were dying to escape. "Turn down the heat" I said so icily that it was if I half believed that my voice alone could lower the car's temperature. I did not even know what my mad was about.

Who doesn’t know the complex love/hate engendered by any meaningful relationship? To me, this is encapsulated by the painful realization that the links that I send people go unopened, the mixed cds I’ve made for lovers remain unheard, the books I gift unread. And of course, of course! We all contain different oceans, have different mixes of salt, silt and stardust contained within our multitudes. And isn’t this sometimes painful? Isn’t it so hurtful to realize not only that we want different things, but that sometimes we will deliberately not give the other person what they want? The struggles that I see so often between best friends cut deep. I could still tell you the first and last name of the first best friend to break my heart, and I remember what the stairs looked like as I descended them after she said she wouldn’t play with me at recess. Heartbreak hurts, and the pain is just as real for children as for anyone else. Here to get you through these times is this beautiful, true book.

Norman Didn't Do It (Yes, He Did)

by Ryan T. Higgins

Here is something that doesn’t get enough play: friend jealousy. Brené Brown distinguishes between envy and jealousy: envy is wanting what someone else has, jealousy is when “we fear losing a relationship or a valued part of a relationship that we already have”. [with thanks to Allison Pilon for this point] Having suffered from intense jealousy of the other friends my friends make and the fear that I will be left behind, I can totally relate to children who feel this way. Jealousy is excruciating, and we should talk about it more.

Bitter, enraged jealousy is the story of Norman and his friend; a tree named Mildred. Norman and Mildred do everything together: they play chess, they hang out, they take the world in together. Suddenly, out of nowhere, a new tree starts to grow. Norman is horrified, frightened and enraged that this new OTHER TREE will take away his friend Mildred. “Suddenly, it was no longer just Norman and Mildred. Now it was Norman and Mildred and the other tree.” Norman worries: what if Mildred liked the other tree MORE than she liked Norman?

So many times I’ve been advised to say to our kids when they are jealous of one another: “you can stay here and still try and play OR or you can go take some space. Those are your choices.” And yet truly, have I ever accepted this devil’s choice myself? No! I’ve usually stayed and tried to ruin the day for everyone with a ferocious cry of “misery loves company!” So too Norman. Norman decides to dig up the new little tree by whom he is so threatened and take it far far away to an island. But then, guilt overcomes Norman. “Remorse! Remorse. It was staring me in the face” (says Julian in the sequel to Wonder).

Norman and Mildred are back together. But “it wasn’t the same.”

Norman tries to justify his actions to Mildred: maybe the little tree went on vacation? Norman becomes defensive: “How should I know?” and then afraid: "what if someone saw?" Until finally, Norman says: “What have I done?” In the best literal sense, Norman tells us, he has hit rock bottom and is pictured lying on a big rock at the bottom of a valley. Finally, Norman goes back to get the other tree. Norman knew life was “going to be different. And that was okay.”

Oh change. Change! It’s so terrifying. And who knows what else. Over dinner, I watched my son watching something outside the window. "What are you looking at honey?" I asked him. “Mummy, the pigeons are having a wedding!” said my youngest son, looking down at two cuddling pigeons. “I hope they don’t mind moving.”

Books like Norman Didn’t Do It (Yes He Did!) help us to support ourselves through jealousy and relational change and, in doing so, to scaffold and support our children.

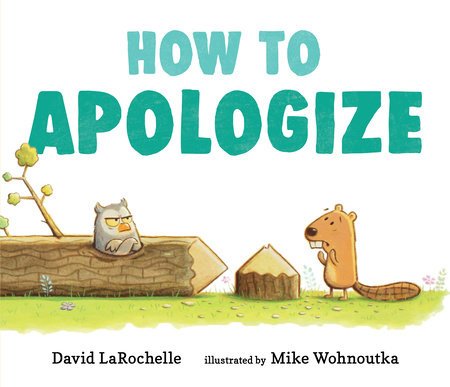

How to Apologize

by David LaRochelle, illustrated by Mike Wohnoutka

All relationships have tears and rents in the fabric. Although repairs consist of a range of threads and patches, they are everything. “It’s all in the repair” my beloved partner and I say to each other often, and it’s true. But repairs aren’t easy and they benefit from explanation as to how to have a skillful one. Here to fill the gap in the social story of How To Apologize is this beautiful book.

One of the trickiest things about an apology is it needs to come alone, without justification. People often want to explain why they failed right away. Witness: “I’m sorry I was late, my dog just needed to go to the vet; I’m sorry I yelled, I was just really stressed out.” And yet, there is so much to be gained by separating the apology from the explanation. It’s like a therapist once said to me, if you say “I really like that but,” basically everything before the "but" has been nullified. The reason we have adages like everyone makes mistakes and nobody’s perfect is because they are true, true in the deepest sense. And so this book begins: “Everyone makes mistakes.” Big or small, well-intentioned or deliberate, we all make them. And this books reminds us how hard it is to apologize. A true, sincere, vulnerable apology is SO hard. It can be hard “if the other person is mad or if it’s someone you don’t like.” And yet, it remains important to apologize….even if the person owes you an apology too. I have remained amazed in my life by how if I start with apologizing for my part in a conflict, how much this allows the other person to rise. How to Apologize is clear “Don’t: make excuses. Do: be sincere.” And then this genius piece of advice: “Even if the mistake happened a long time ago, it’s never too late to apologize.” I sent a facebook message a year or so ago to someone I bullied when I was 8. I got the most generous reply, it brings tears to my eyes even now: “I don’t remember it quite like you do, but if you’re this sorry now, I know you were sorry the minute after you said it.”

“If possible,” the book asks us, “try to fix the mistake.” But “sometimes you can’t. In that case, you can still say you’re sorry, then take steps to avoid making the same mistake again.” And the reason we apologize is that it may make us feel better, but “More importantly, it will make the other person feel better. And that’s why we apologize.” This is wide advice, wise advice for everything from spilled milk to saying a systemically hurtful thing. We need to apologize and listen, this too is the truth as I have learned it.

Witness: I recently was stressed, grumpy, a million undone things seemed to press at me. "Get in the car" I said in a harsh voice at the same time as my youngest son said with wonder: “Mummy, don’t you think that if flowers bloomed in winter it would be so beautiful with the snow?” It seems to me an apt metaphor – the tiny breathless things that still dare to raise their heads in what can feel like a cold, cruel world. And yet, it is spring, here we are again. Braving the elements, all of us raising our tiny heads separately and together. “I’m sorry I snapped at you, you’re right, they would be beautiful.” "That’s ok mommy," said my youngest son forgivingly.

A friend of mine regularly quotes the picturebook And Then It's Spring, in which a child puts up a sign for a garden they have planted that says: "Please do not stomp here -- there are seeds and they are trying!" As we move forward into these beautiful, long and light-filled days of spring, I hope these books give you too the strength to apologize and to mean it, to give yourself compassion when you make a mistake, and to keep trying in the repair.