On Anxiety Again

I am so tired of anxiety. I’m tired of feeling anxious and I’m tired of there being so much to be anxious about. Anxiety seems to me antithetical to enjoying the moment. Anxiety in children and in adults too is deeply connected to time and one’s experience of being in time, what Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls being in “the flow”. Violinist Natalie Hodges explores flow states in her beautiful book Uncommon Measure: a meditation on racism, performance anxiety, and time. Hodges describes an experience of performance anxiety where one moment she is in time, in the moment, playing the music, and then all of a sudden she becomes aware of the audience and time start to freeze:

"It’s (almost) comical now, but whenever I think back and try to analyze what happened, I am still stricken by the memory, sick and visceral, of how it felt when time stopped. Why is it that one’s sense of time, so supple inside the music itself, seizes up and cracks beneath an audience’s expectant gaze (or as soon as one becomes aware of that gaze, that expectation)? Why does getting into the flow of music require yielding yourself to its time, feeling its flow through and around you, when all the while time is also the enemy, the thing you’re running out of as you play along, trying to make it to the end and yet trying to make something of the moment while the music lasts? . . . If you can’t get into the flow – if your nerves get the best of you and you’re dragged onto the shore of self-consciousness – the flow is staunched, the fabric rent, you feel punched in the gut, knocked out of the music’s time and back into your own. And then, afterward, you can feel the seconds and minutes passing; you trudge through, it’s all linear, you just want it to be over, you just want to make it to the end."

This kind of reminds me of having young children, the seconds tick by sooooo slowly, the years stream so fast. It seems impossible to enjoy the moment until it's over and you long for it to return. So too have I seen this with anxious children. Children feeling anxious can’t manage to stay in deep play. This seem to me epitomized by one of my children as he coloured in a drawing: “I want to finish so many drawings, but I have so little time left!” he said to me in a state of agony. This is one time among many when I longed to say: “Don’t finish coloring then, what does it matter?” but instead drew on deep wells of I don’t know what to say 'I hear you're feeling anxious.' 'Of course I’m anxious!' he said. 'I need to finish my vision!' Makes sense. Why do I stress about how long it takes me to empty the dishwasher? When it is emptied the moment will be over and I’ll be one second closer to death, by that logic.

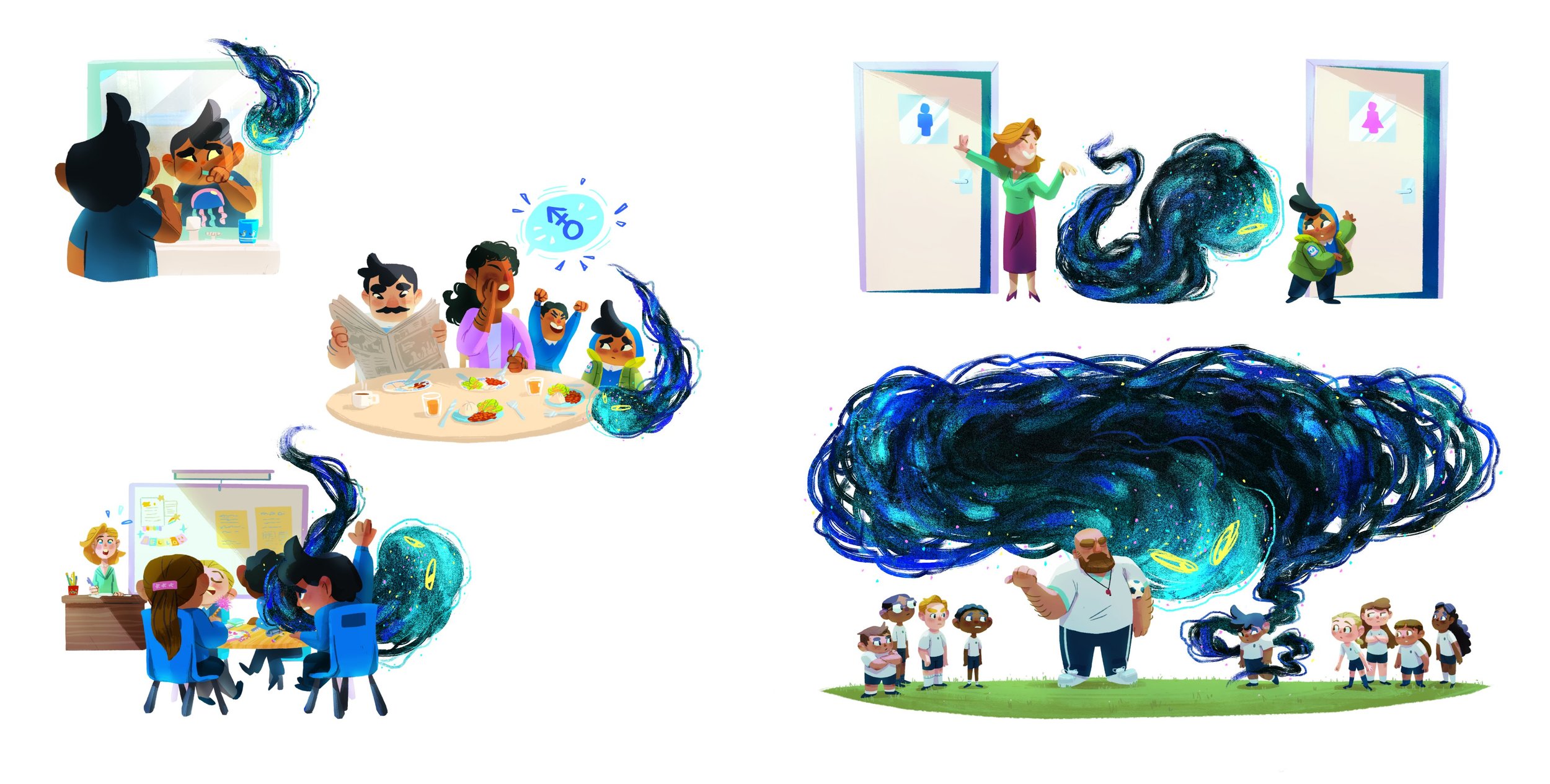

from My Dysphoria Monster, by Laura Kate Dale, illustrated by Hui Qing Ang

I’ve seen children who are truly involved in some game when all of a sudden something interrupts it – an anxious thought, the feel of adult eyes on them – and they are out of the timeless nature of deep play and into the self-conscious time of anxiety. Dragged back into worrying about the night ending and the school day beginning, or a swimming pool swimming towards them, or bedtime and its attendant fears of monsters and the dark. “Oh, let it be over,” said an anxious child who is close to me. Meaning, this moment. Meaning, anxiety. Let it all end. How existential and of this moment all at once.

Anxiety these days is big. And luckily there are lots of tools that we can use to help our children. In her excellent and free class on anxiety in children, available on youtube, psychologist Adrienne Matheson talks about the kids who have overactive security guards in their brains. Matheson suggests helping children to unpack their anxiety using the thought/feeling/fact triangle:

What is the anxious thought? (I won’t have any friends at school).

How does that make you feel? (Scared, embarrassed, ashamed.)

Is this true if we fact check it? (No, one of my friends always sits with me. Even if I don’t have lots of friends, I like playing with her.)

from There Must Be More Than That by Shinsuke Yoshitake

Sometimes this works and sometimes it doesn’t. My life’s work along with many others is building a feminist approach to children’s mental health. Anxiety is individual and it is also systemic: systemically caused and as a result we need to systemically address it. Here are 4 books that meet all the criteria: children like them, they offer concrete psychotherapeutic education as to how parents can help their specific children, and they offer a systemic critique of how anxiety presents differentially.

Me and My Dysphoria Monster

by Laura Kate Dale, illustrated by Hui Qing Ang

If we need more books that talk about anxiety as systemic, here to help us do so is Me and My Dysphoria Monster. This book is special because it uses monsters and so all the kids – even the tough boys – like it. It’s succinct and it’s uplifting. While there may be no perfect strategy for anxiety, a bit of attuned psychoeducation can go long way. (As Dr. Becky Kennedy says: “I can’t change the hard but I can change the alone.”) What do queer and trans children need from the grownups around them? “Unconditional positive regard,” says the book Queer Psychotherapy. Adults who delight and accept them “just for being themselves” in the words of the gentle visionary Mister Rogers. Me and My Dysphoria Monster features a little trans girl named Nisha. She is followed around by an anxiety monster, much like Emily of The Whatifs (next). But unlike Emily, Nisha’s monster gets worse related to her gender dysphoria. Although Nisha’s monster follows her everywhere, playing with her friends, hanging out with her cat, her anxiety monster especially grows in size when she is misgendered: when she is called by a boy’s name or told she must play on the boys’ team. Eventually Nisha’s dysphoria monster grows so big that she can’t even swim in the ocean or hang with her friends. Then she meets Jack, a trans grownup who tells Nisha about how talking to people who loved him “just for being himself” helped quite a bit. After she tells her family and her teachers, and after people start using the right pronouns and let Nisha use the “girls’ toilet at school” and “play on the girls’ team,” her monster shrinks and shrinks until it is only the size of a pea.

It's a hard time, it’s a hard time on this stuff, in Ottawa and everywhere. I read a book at a school last week. I’d picked it because a princess boy I’d noticed for the last year or so complained with so much pain about how much he wanted to wear dresses. “I know, I hear you,” his wonderful attuned teacher said to him. And yet I sensed his anguish as he said “my mother says no dresses ever.” He looked tense and unhappy this year, and I had brought in a book called Princess Boy just for him. "I am a princess boy" he yelled at the end of the book," and a little boy who sat beside him said gently: “Princess boys are the best. I’ll play with you.” Children are so good, so kind, so noble, before we take all that away from them. Let us follow in their wake.

The Whatifs

by Emily Kilgore, illustrated by Zoe Persico

Here to talk us through the challenges of anxiety is the book on performance anxiety Emily and the Whatifs. In this book, Emily is filled with anxious monsters she names the whatifs – hers come in all different shapes and colours. They are there to taunt her: what if you play a wrong note at the recital? What if everyone laughs at you? The more Emily worries, the more her whatifs grow. The thing about anxiety is it is more likely to make you see the world in a negative light. This is why anxious children often miscue their parents by expressing feelings of anger or terror, rather than saying "I feel anxious." As Emily struggles, another child notices. When Emily shares her worry, the other child manages to gently guide her back: "What if there is cake after the recital? What if you play well?" And, as the book ends with Emily making a mistake in her recital and recovering, the book concludes with Emily wondering: “what if I made a new friend?”

I was recently very anxious about something that I can’t even remember. Confiding my worries to a close friend and referencing a book I’d previously shared with her, she said to me gently “there must be more than that. There must be more than the world ending or everything working out.” Here too is a book that models how to challenge worried thoughts with kindness and compassion, and models reaching out. Seek wise consel says writer Ann Lamott, and generally, this is proven to be true.

All About Worries and Fears

by Felicity Brooks and Mar Ferrero

This book lacks narrative. It’s also a little hard to find. But it is helpful. It explains things to children and it does not need to be read in one go. I have found that for children who don't have anxiety, they can’t bear to have it read to them. And for a child with anxiety, they will sit riveted through a shocking number of fairly dense pages, and I can tell they feel it is speaking directly to them. This book really examines the wide range of feelings worries and fears can produce in the body. (Like a huge bag on my back weighing me down. Like I’m trying to walk through thick, sticky mud. Like I have a washing machine inside my tummy.) It explains clearly fight, flight and freeze (and even gestures towards “fawn” and “fix” trauma responses) and it has creative ideas for what to do. “Build the tallest tower of cushions you can and then knock it down. Get busy, make or do something, go outside, get your body moving.” In short, it provides lifelong coping mechanisms for people to try. It also gives parents tips on how to validate their children. (For a great book on how to listen to children, check out The Rabbit Listened).

Listening, listening. Before I was a parent and I just practiced telling everyone what to do all the time (which made me very popular), I thought I’d be an excellent listener. In a couples therapy session, my partner kept saying to me "I just want to share my feelings and I want you to listen." I had a hundred reasons why I couldn't: "the kids, I can’t, I’m too overwhelmed myself." Finally, the therapist said to me (not even that gently): "don’t you know how to validate?" You know, I do. But I had no idea it would be so hard. I have to validate the most ridiculous things! Nobody told me I would have to do that. “No, witches can’t look inside the window and see you naked. No, monsters don’t eat the teeth that fall out of your mouth. No, there won’t be a needle at the carwash where we are headed.” Ag. All the times of worry big and small. It is not fun, it’s boring, frustrating, and super annoying helping anxious children to face their fears. And yet, here we are: "I hear you, you're feeling anxious" remains the sentence that works the best.

The Good Egg

by Jory John & Pete Oswald

Sometimes I feel like I wish every book or every person talking to caregivers about their children’s anxiety would say first (validate!): “hey caregiver, I know I am asking you to do YET MORE. Say this, not that. Listen. Validate. Rinse and repeat.” One of the things I appreciate about The Good Egg is that it feels equally directed at parents and children. I have previously written about The Bad Seed here, and of course The Good Egg serves as a companion. Keep track of when you are inauthentically “being good,” said my therapist to me. How could I keep track? Most times when I’m "being good" it feels inauthentic I wanted to say but didn’t. I identify with the good egg, who is pretty focused on telling everyone how good he is. (Because how else would they know?)

The Good Egg begins with the good egg’s good deeds: “Oh hello! I was just rescuing this cat.” And lest we fill in the gap incorrectly, the good eggs leaves nothing to the imagination: “Know why? Because I’m a good egg.” The good egg then shows all the good things they are up to. It’s clear that the good egg’s help isn’t always as well received as perhaps they think it is. Hence some overwatered plants and a badly painted house. But the good egg is challenged in their desire to be good by a dozen difficult siblings. The whole carton does not share the viewpoint of the good egg. Rather than being good, the siblings are BAD. They swing from the chandeliers and draw on the walls. They resist the good egg’s efforts at every turn. Finally, the good egg burns out from all this bad when the good egg is just trying to make everyone be good: “My head felt scrambled,” and one day “some cracks” appear “in my shell.” The good egg realizes that it’s all too much, and the doctor tells them “that it’s from all the pressure I was putting on myself.” Like me, the good egg is somewhat of a control freak, and wants everyone to be just as good as them. But, something had to change. Haven’t we all felt this? That things just cannot continue as they are for One. More. Minute. In this case, the good egg is “cracking up . . .literally! Knowing that something has to change, the good eggs leaves the carton. The other eggs don’t seem to care: “’I can’t be the only good egg in a bad carton,’ I said. ‘Blah Blah Blah,’ they replied.” So the good egg sets out on a quest. Taking walks, reading books, floating in the river, painting and resting. And “guess what! Little by little, the cracks in my shell started to heal. My head no longer felt scrambled.” So the good egg makes “a big decision. I’m returning to my old carton and my friends. . . .I’m kind of lonely out here.” But this time, “I’ll be good to my fellow eggs while also being good to myself.” Here’s what I’ve realized, the other eggs “aren’t perfect, and I don’t have to be, either.” Maybe it’s not always easy, but “I’m OK with that.”

I often wish there were more words for the fights we have in cars. That truly horrible feeling when the tension is building but there is no where to go. Fights are often worse when we feel trapped. So many times, I’ve wanted to open the window and fly out myself. It’s an anxious time, and cars are anxious and trapped places. They may as well be the liminal spaces between joy and grief, between here and there, between living and existing. We were in one such place, in a lineup for a drive-through, as the tension built and built until we arrived and they did not have the desired treat. As things started to break down, I pictured the kind of parent I want to be, and the kind of parent I was feeling like. Co-regulate, co-regulate seemed to be smashing its way through my skull, as I tried very hard not to say “seriously? You’re mad because of a lack of donut holes? Have a DONUT!” And yet who am I to say what “super sucks” and what does not. Who am I to try to be the good egg in the carton.

When we arrived home, my youngest son placed his hand gently on my arm. “I’m so so so proud of you mummy, he said. “You were so so patient.”

In Birds, Art, Life, Kyo MacLear tells this story about her cautious son:

"At the end of May, when fewer birds migrated through the night sky, my younger son awoke from a dream and climbed into our bed, exhausted and exhilarated. He had dream he was on a giant tree swing, rising higher and higher, past his waking terror of heights.

It felt like flying, he said, pointing to the phantom soaring feeling in his chest.

Did you fall? I asked.

No.

Did you jump?

No, he said, hesitating for a moment. But next time I think I will.

I couldn’t tell if he really meant this, if he felt brave or he thought I might wish for a braver son. It didn’t really matter. It was a good dream.

Later I will tell him: our courage comes out in different ways. We are brave in our bold dreams but also in our hesitations. We are brave in our willingness to carry on even as our pounding hearts say, You will fail and land on your face. Brave in our terrific tolerance for making a hundred mistakes. Day after day. We are brave in our persistence."

Anxiety is so complicated. It is inevitable and it can be soul-destroying. It is meted out unequally. Anxiety is also painful: “it hurts, it hurts,” said my son crumpling a dragon drawing that did not match the dragon in his mind. “My heart hurts so much I can hardly stand it." And yet stand it we do, like grief, like rage, like injustice. We stand it and stand it until our faces feel frozen in smiles. These books feel like candles in the dark, like hugs, like signposts to the things that say “this too shall pass” and “justice will arrive” and “some day you will really feel better, not just say you do.”

Intimacy is fundamentally entangled with sadness, with vulnerability, with anxiety, with exchange, reminds Natalie Hodges in Uncommon Measure: A Journey Through Music, and it is as imagined as it as real. And this too is a good dream, one worth striving for. I recently was anxious about reading a book to my son's class. It wasn't smooth. I had trouble turning the pages and kept mispronouncing words. Reading the book was a success and a failure and an embarrassment and a lot of fun. And here is why it was a success. I turned to the final page of the story, and a little tear leaked from my eye. And so I knew I was reading it with them in the present, for real.

Until soon,