On Grief & Connection

“For nothing was simply one thing” - Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse

This is one of my favourite quotes – it seems to me to be in praise of ambiguity. Alison Bechdel uses it to begin her memoir Are You My Mother? and to me it speaks deeply to the paradoxical nature of parenthood. So many moments simultaneously endless and fleeting, every stage agonizingly slow and then over all too soon.

When one of my sons was a baby, I was making food for myself and it was suspiciously quiet. I had never before experienced suspicious quiet, since I was a new parent. To me, it was just quiet and it was welcome. “Aaaaah,” I thought, “a moment of respite”. And then of course I caught sight of my son to whom I had given a bag of rice. He had broken it open with his teeth and was busy grinding it into the spaces between the floorboards of the borrowed apartment where we were living. AAAAH!!! I thought as he grinned at me delightedly. And yet, I’d give anything to have that morning back, when he was a tiny baby and the worst thing happening was rice on the floor. What a complicated place life is. We consistently wish moments over that we then immediately long to have back. We are such complicated creatures.

One of my profound needs during this challenging time is to both make and find meaning in its attendant sadnesses. One of the paradoxical things about grief is that it can bring us together – it can lead us to what writer Susan Cain calls “a union of souls” in her beautiful book Bittersweet. Speaking of how we all contain such deep longings, Cain describes how they are often connected to sadness, to yearning, and how these feelings of great aches for what she calls the "unreachable perfect world" can happen through art, through music, through nature. These gateways help us to see that our sadnesses are also guides: they guide us to spaces where we notice “that the world is sacred and mysterious, enchanted even.” The places we yearn for have many names: from “Somewhere Over the Rainbow" to "Home" to, as Cain notes "the novelist Mark Merlis puts it, “the shore from which we were deported before we were born.” And grief can transport us to those places together – in sharing grief and yearning, we can connect, because “The place you suffer . . . is the same place you care profoundly – care enough to act.” These portals are everywhere: a glowing raindrop or a haunting melody – all of these can serve as gateways to that for which we long. For me, the gateway to my "perfect, unreachable world" is picturebooks. Picturebooks are art objects: they are collections of paintings and poems and they are tributes to complexity that are helping me personally to make meaning out of this difficult time. In the spirit of nuance, meaning and grief, here are 3 books that help us to see that everything is truly more than one thing.

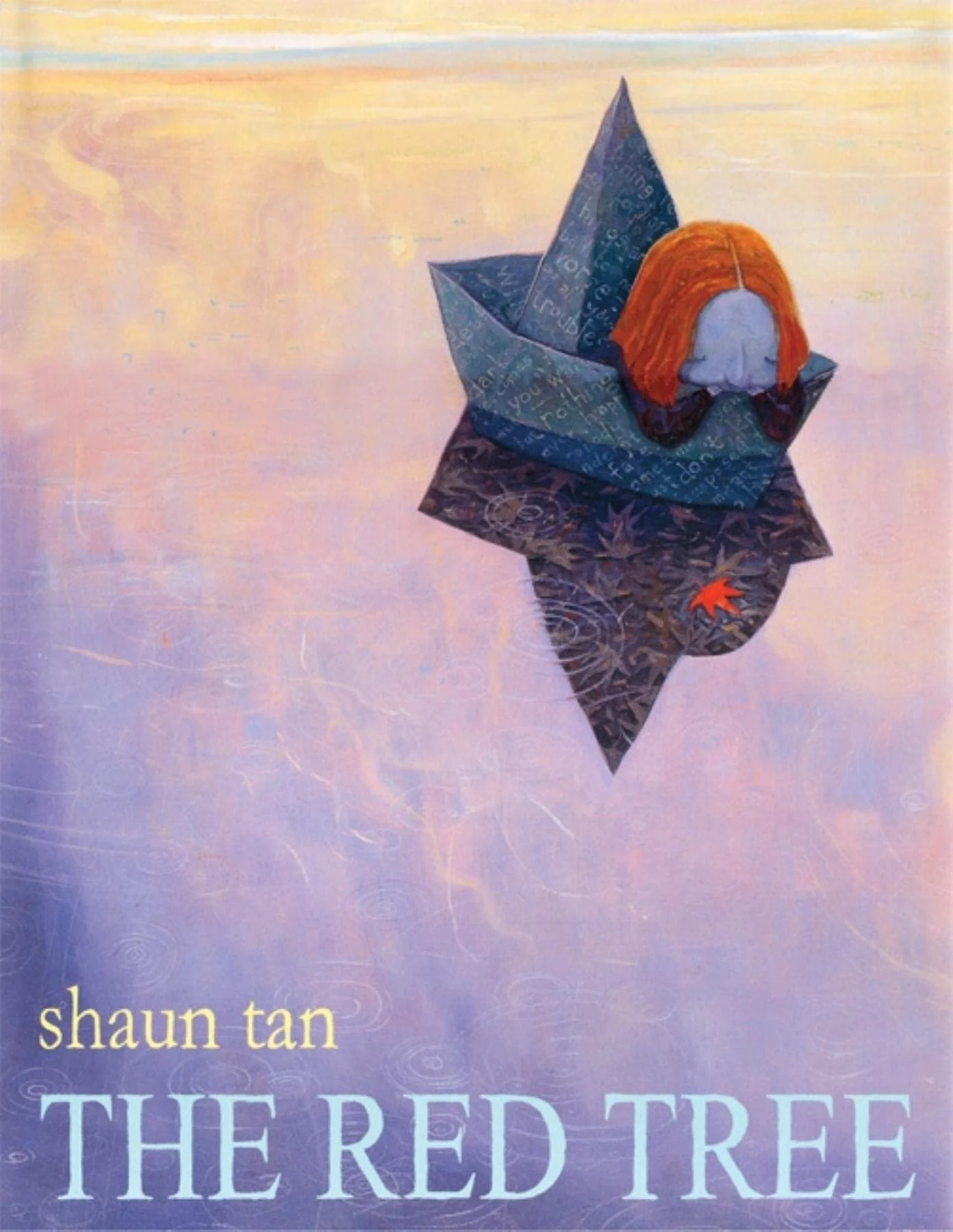

The Red Tree

by Shaun Tan

I include this book because I struggled with what I now think was some kind of combination of anxiety and depression in graduate school. The uncertainty of the academic job market, the long, lonely days of writing my thesis. I would call my mother every morning and complain into the phone. And my amazing mother, bless her, would listen and listen and listen and listen and listen and validate and validate and validate and validate. Boy, did I ever *not appreciate* how hard a job that was then, and do I ever appreciate it now. I regularly read The Red Tree to myself in graduate school. More than fifteen years later, my sons like it too. To me, it does the best imaginable job of explaining some of the characteristics of depression. I tend to get my sadness in the morning, so the first line really speaks to me:

Sometimes the day begins with nothing to look forward to

and things go from bad to worse

I see it in my sons too. A case of the Sunday night blues, or a case of the Mondays. Unexpected tears and a general sense of ennui. They wake up with difficulty and kind of lie around looking demoralized. What a contrast to the Saturday wakeup! The Red Tree is there to remind us that sometimes the world can feel like a cruel machine “without sense or reason,” or that “sometimes you wait and wait and wait and wait and wait, but nothing ever happens.” Sometimes it seems that “all your troubles come at once" or that "Wonderful things are passing you by." Or as if "you just don’t know what you are supposed to do or who you are meant to be.” It’s true, isn’t it? It’s true. Years ago I wrote about this graphic novel about depression (Hyperbole and a Half found here) and when you have big sadness there can be simultaneously a too-muchness of time and too-little fun time. Part of what I find with grief and sadness and depression is a clock that doesn’t work quite right. For all the kids who experience clinical depression and for all of us who experience grief and big sadness (which is to say, all of us), here is the book that makes a person feel very seen. And also, in the tradition of hopefulness and earnestness that I so appreciate in children’s picturebooks, The Red Tree reminds us that

suddenly there it is

right in front of you

quietly waiting

just as you imagined it would be.

“I only like Sundays,” said one of my sons. “It’s the only day where we don’t have to be anywhere or do anything and it’s usually good the whole day long. Except when it isn’t at all.” And yes, I wanted to whisper. Life is full of tiny little moments of sunshine and rainbows and unexpected treats and flowers that open so slowly and then bloom all at once. Except when it isn’t at all. And here for those moments when it isn’t the is The Red Tree.

Out of a Jar

by Deborah Marcero

This book is pure genius. It is artful, beautiful, and explains the dangers of becoming shutdown. That is, Out of a Jar explains how when we shut down our grief we also shut down our joy. “Anxiety is sublimated grief,” said my brilliant therapist of 20 years. And here to help encourage us to feel our feelings is this book. It start with Llewelyn, a little bunny who likes scary movies and scary costumes, but doesn’t like feeling afraid. He’s sick of feeling afraid at night, and so he puts his fear in a jar, and then takes it down down down some stairs to a sort-of basement to “lock it away,” and “that was that.” Each uncomfortable feeling that Llewelyn has: loneliness, disappointment, grief – all these go in jars too. In keeping with the strange truth that being happy is as vulnerable as being sad (in fact, people struggling with addiction are as likely to use when they are feeling really up as they are when feeling really down), even Llewelyn’s joy and excitement seem to overwhelm the people around him. So he is forced to put those feelings into jars too: “and that, was that.” But finally, Llewelyn can’t take it, he can’t take it one minute more. Nobody, it seems, can bear his big feelings. “Soon he had so many jars filled with so many emotions that Llewelyn walked around feeling not much of anything at all.” This is one of the things that scares me about raising sons. Please, please, let them continue to feel. Delight, grief, disappointment, loneliness and joy. Let them never be told to "walk it off" or not to cry. I fear the comfortably numb fog of toxic masculinity consuming them until they don’t even know what they feel.

When Llewelyn is shamed in front of the class for a beautiful art project he makes, he is embarrassed: “He tried not to show it but that just made it worse.” When he goes down to add one more jar to his basement and lock the uncomfortable feeling away, there is no more space. “Something rumbled deep inside of him” and all of those feelings “broke loose and pummeled Llewelyn with a stampede that turned him into a ragged heap of bunny onto the floor.” And “Buried at the bottom, fear was the last to leave. After his feelings return, something “happened that Llewelyn did not expect.” He feels more than one thing at once: he was “happy and sad” or “excited and worried”. And so Llewelyn musters up the courage to feel and share his feelings, and “when he was ready, to look each feeling in the eye, give it a hug, and let it go.” And, friends, “that, really was that.”

I can’t recommend this book enough. "Sometimes I feel sad honey," I said to one of my sons. "I feel sad about some of the things that happened in our family." "Just put your feelings in a box mummy," said one of my sons. "That’s what I do." I tried to explain: but when you shut out the sadness, you shut out the joy. You can’t turn down the volume on only the hard feelings without losing the happy ones as well. And here, along with The Heart and the Bottle, to explain the dangers of being shut down is Out of a Jar.

Jenny Mei is Sad

by Tracy Subisak

One of the things about being sad or anxious when you are a child is that you can miscue your parent. You can act angry when you are actually worried. Jenny Mei is normally a nice person: she shares her snacks, she’s warm and kind, and she includes all the kids in her funny jokes. Except when she is not nice at all. Sometimes Jenny Mei is cruel and mean without warning, tearing up a beloved drawing of another child in her class for no reason. Something I have found profoundly mysterious as an educator and a parent is how often children miscue the adults in their lives. It is so hard to know what is underneath! Jenny Mei’s teacher has figured it out. She takes Jenny Mei outside to talk about her feelings, and when Jenny Mei comes back into class she is feeling better. This book is about the profound friendship between children. Through all her up and down emotions, Jenny Mei’s best friend, the protagonist of this amazing book, understands and loves her. As she says, Jenny Mei “knows I’m here for fun and not-fun and everything in between."

Oh, children are so wise. We are in a cultural moment, myself included, that is about walking away. Ghosting, leaving… it seems that a new person can be had with the push of a button. But these two girls understand the depth of their bond and the importance of sticking out the ups and downs. I myself can be quick to walk out the door whereas my partner is steady and steadying; I have much to learn from her. On the very last page, Jenny’s Mei’s door opens and a caregiver is there who looks like they are seriously ill. It becomes clear that Jenny Mei is struggling with the unfair burden of impending loss. In a beautiful review in the Wall Street Journal, it says that “Those who are sad, Ms. Subisak shows with kindness, don’t always behave as we imagine they should. Sad people may lash out in their misery and, indeed, feel swept away by loneliness and sorrow.” So true.

In many ways I write this blog for my mother – the big love of my life and my most beloved and adored reader and muse of projects big and small. The tenacious umbilical cord – that which we adore and which drives us crazy as we do too to our children. I yelled at my son last night for deliberately breaking his electric toothbrush – the third such brush we have bought this year. The first fell prey to strange hotel rooms as I brought it in an attempt to be responsible, to use less plastic, only to forget it and thus throw away more plastic than ever. This third unlucky toothbrush met an untimely end as my son banged it against the bathroom counter to see if it would break (it did). "Well mummy, I guess it’s not the year of the toothbrush," he said to me, and I had to agree. In all ways big and small, it certainly is not. And yet here we are, together and apart, making meaning of all of the broken toothbrushes of this big, beautiful world.

Oh, life. What do I want from it sometimes, I don’t know. To feel deeply and to have the courage to face my most difficult feelings, and to have that be true for everyone else as well. To have someone who will listen to my fun and not-fun and everything in between. The truest thing about sadness is that it connects us – it is scientifically proven to do so. Moments of shared grief can allow for a “union between souls” as author Susan Cain would put it. And I also wish for all of us that we continue to be able to pause and to take in the joy. I’d left a book out the other day, one of the amazing books that are illustrated by Barbara Reid with the most marvelous plasticine pictures. I was busy making dinner and ordering groceries and doing all the things when I heard my youngest son say something, and he was looking through the very book I’d left out for him. "Look at this mummy," he said. And I started to say I’m busy but something stopped me and I walked over. "Aren’t these illustrations beautiful" he said. Oh! And to share something like that together. That brief moment of looking separately and together simultaneously. Looking out both his and my eyes – it brings tears to mine even now. Those moments of connection are so ephemeral and rare and so, so meaningful. There are so many moments like this in life and at the same time too few. I am so glad I had this one, and I hope these books give you too the chance for more of them.

I leave you with this image that we looked at together. I hope it lights your way forward during the day as it did ours.